Helen's Teacher: The True Miracle Behind 'The Miracle Worker'

Anne Sullivan's Groundbreaking Educational Approach

The story of Helen Keller and her teacher Anne Sullivan is one of the most inspiring tales of perseverance and education in history. While Helen Keller's name is widely recognized, the woman behind her remarkable transformation often receives less attention. Anne Sullivan, known as "The Miracle Worker," played a pivotal role in unlocking Helen's potential and helping her overcome the challenges of being deaf and blind.

Sullivan's own background shaped her approach to teaching Helen. Born with poor eyesight and raised in poverty, she attended the Perkins School for the Blind where she learned to read and write. This experience gave her unique insights into the world of those with visual impairments. When she arrived at the Keller household in 1887, Sullivan faced the daunting task of reaching a child who had been cut off from the world since infancy.

Through innovative techniques and unwavering determination, Sullivan broke through Helen's isolation. She used tactile sign language, spelling words into Helen's hand, and connected physical objects with their names. The breakthrough moment came when Helen understood that the word "water" Sullivan was spelling corresponded to the liquid flowing over her hand. This opened the floodgates of communication and learning for Helen, setting her on a path to become an author, activist, and inspiration to millions.

The Life of Annie Sullivan

Annie Sullivan's remarkable journey from a challenging childhood to becoming Helen Keller's groundbreaking teacher shaped her into an extraordinary educator and advocate.

Early Years and Education

Born in 1866 in Massachusetts, Annie Sullivan faced significant hardships from a young age. At five, she contracted trachoma, an eye disease that severely impaired her vision. Poverty and the loss of her mother further complicated her early life.

Sullivan's fortunes changed when she entered the Perkins Institution for the Blind at age 14. Despite her initial lack of formal education, she quickly excelled academically. Her determination and intelligence helped her overcome the challenges of her visual impairment.

At Perkins, Sullivan developed the skills and knowledge that would later prove crucial in her work with Helen Keller.

Challenges and Triumphs

Sullivan's path was marked by numerous obstacles. The loss of her brother Jimmie, her only sibling, deeply affected her. She also struggled with multiple eye surgeries and ongoing vision problems.

Despite these setbacks, Sullivan's resilience shone through. She graduated as valedictorian from Perkins in 1886, a testament to her academic prowess and determination.

Her greatest triumph came when she accepted the position to teach Helen Keller in Tuscumbia, Alabama. This decision would change both their lives forever.

The Journey From Tuscumbia to Radcliffe

Sullivan's arrival in Tuscumbia marked the beginning of her legendary work with Helen Keller. She quickly established a strict regimen of discipline and education for her young student.

Her innovative teaching methods, including finger spelling and outdoor lessons, proved highly effective. Sullivan's patience and perseverance helped Helen make remarkable progress.

As Helen's education advanced, Sullivan accompanied her to various schools, including Radcliffe College. She attended classes alongside Helen, transcribing lectures and helping her navigate academic challenges.

This journey showcased Sullivan's unwavering commitment to Helen's education and independence, solidifying her reputation as an exceptional educator.

Helen Keller and Annie Sullivan: An Unbreakable Bond

Annie Sullivan's arrival at the Keller home in Tuscumbia, Alabama marked the beginning of a remarkable partnership. Their relationship transformed Helen Keller's life and left an enduring impact on education for the deaf-blind.

Meeting Helen Keller

Annie Sullivan met Helen Keller on March 3, 1887. Helen, then six years old, had lost her sight and hearing at 19 months due to illness. The young teacher faced a challenging task - to connect with a child trapped in a world of darkness and silence.

Sullivan's own experiences with partial blindness gave her unique insight into Helen's struggles. She approached her pupil with determination and compassion, recognizing the intelligence hidden behind Helen's frustration and outbursts.

Overcoming Communication Barriers

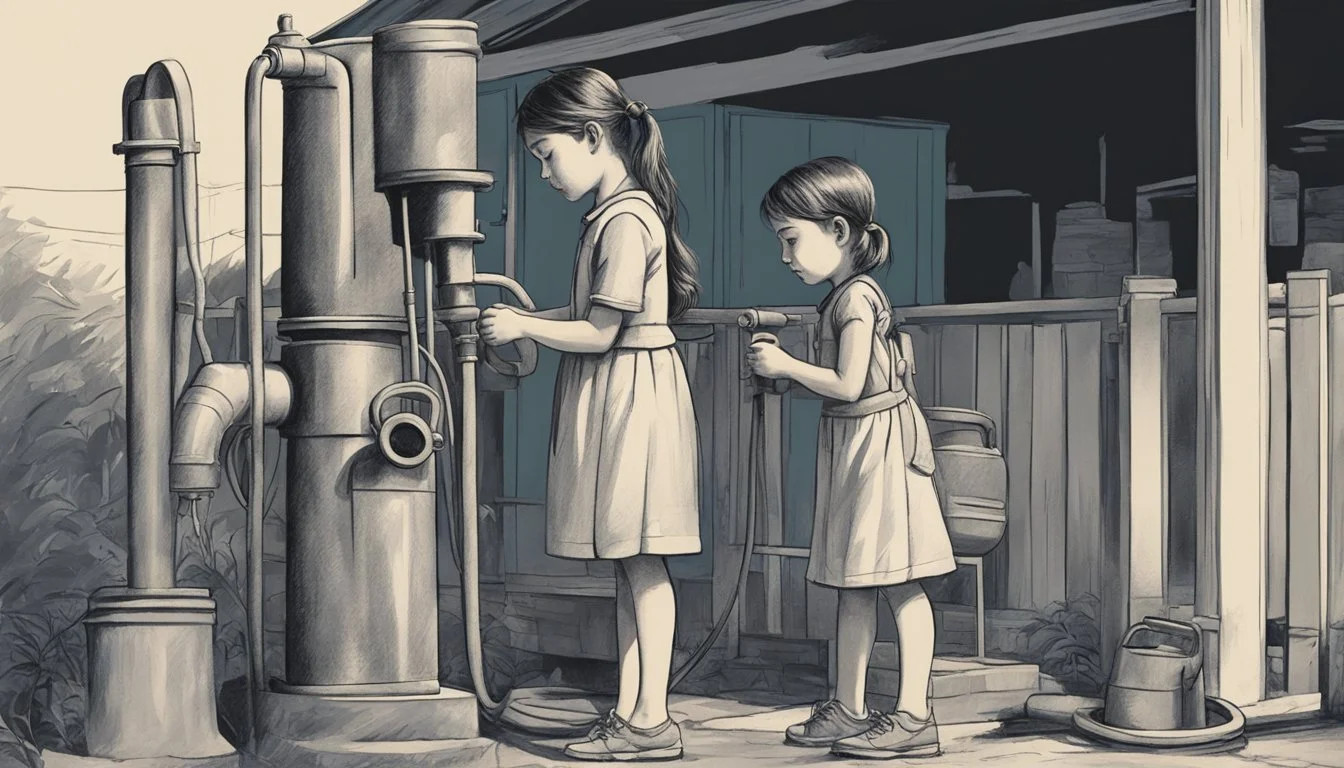

Sullivan's breakthrough came when she helped Helen associate words with objects by spelling them into her hand. The famous moment at the water pump, where Helen understood the connection between the flowing water and the word "water," opened a floodgate of learning.

Sullivan tirelessly worked to expand Helen's vocabulary and comprehension. She introduced the manual alphabet and Braille, giving Helen access to language and literature. Their hands became a bridge to the world, with Sullivan constantly spelling words and concepts.

This intensive one-on-one instruction allowed Helen to make rapid progress in reading, writing, and speech.

A Lifetime of Advocacy

The bond between Helen and Annie extended far beyond the classroom. Sullivan became Helen's constant companion, interpreter, and friend. Together, they traveled the world, advocating for the rights and education of the deaf-blind and visually impaired.

Helen's achievements, including graduating from Radcliffe College, were made possible by Sullivan's unwavering support. They collaborated on books and lectures, bringing attention to the capabilities of people with disabilities.

Their partnership with the American Foundation for the Blind further advanced opportunities for the visually impaired. Annie Sullivan's dedication and Helen Keller's determination inspired generations, proving that disability need not limit human potential.

Annie Sullivan's Educational Methods

Annie Sullivan pioneered innovative techniques to teach language and communication to Helen Keller, a deaf-blind child. Her methods emphasized tactile learning, repetition, and perseverance.

The Introduction of Language

Sullivan's primary focus was introducing language to Helen through touch. She used finger spelling, tracing letters on Helen's palm to form words. This manual alphabet became the foundation of their communication.

Sullivan constantly spelled words into Helen's hand, connecting objects with their names. She persisted even when Helen didn't grasp the concept initially.

Water was the breakthrough moment. Sullivan pumped water over Helen's hand while spelling "w-a-t-e-r", helping Helen understand that objects had names.

Discipline and Perseverance

Sullivan implemented strict discipline to manage Helen's behavior. She insisted on proper table manners and curbed Helen's tantrums.

Consistency was key. Sullivan repeated lessons tirelessly, believing in Helen's potential to learn. She pushed Helen to attempt tasks independently, fostering self-reliance.

Sullivan's determination matched Helen's. She refused to give up, even when progress seemed slow. This mutual perseverance led to remarkable achievements.

Legacy in Education for the Blind

Sullivan's methods revolutionized education for the deaf-blind. The Perkins Institute for the Blind, where Sullivan trained, adopted many of her techniques.

Her success with Helen demonstrated that deaf-blind individuals could learn and communicate effectively. This challenged prevailing beliefs about their educational potential.

Sullivan's approach emphasized experiential learning. She took Helen outdoors, letting her touch and explore nature. This hands-on method became a model for future educators.

Cultural Impact and Representation

Anne Sullivan's story as Helen Keller's teacher has left an indelible mark on popular culture, inspiring numerous adaptations and earning critical acclaim. Her methods and dedication have influenced educational approaches for individuals with disabilities.

Adaptations of 'The Miracle Worker'

William Gibson's play "The Miracle Worker" has been adapted multiple times for stage and screen. The 1962 film version, starring Anne Bancroft as Anne Sullivan and Patty Duke as Helen Keller, brought the story to a wider audience. This adaptation received critical acclaim and box office success.

Broadway productions of the play have been revived several times since its original 1959 run. Television adaptations aired in 1979 and 2000, reaching new generations of viewers. These adaptations have helped maintain public interest in Sullivan's innovative teaching methods and her relationship with Keller.

Awards and Recognition

The 1962 film adaptation of "The Miracle Worker" garnered significant acclaim. Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke both won Academy Awards for their performances as Sullivan and Keller, respectively. The film also received nominations for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay.

Anne Sullivan's contributions to education and disability rights have been recognized posthumously. She was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1973, honoring her groundbreaking work with Helen Keller and her advocacy for individuals with disabilities.

Influence in Literature and Film

Sullivan and Keller's story has inspired numerous books and documentaries. Helen Keller's autobiography "The Story of My Life" details Sullivan's teaching methods and their transformative impact. This work has been translated into over 50 languages, spreading their story globally.

Films and documentaries about Sullivan and Keller continue to be produced, exploring different aspects of their lives and relationship. These works often highlight Sullivan's perseverance and innovative teaching techniques, presenting her as a pioneer in special education.

Sullivan's methods have influenced educational approaches for students with disabilities. Her emphasis on experiential learning and individualized instruction remains relevant in modern special education practices.

The Enduring Legacy of Annie Sullivan

Annie Sullivan's impact extended far beyond her lifetime, shaping education and inspiring generations. Her dedication and innovative teaching methods continue to influence approaches to special education today.

Posthumous Honors

Annie Sullivan Macy received numerous accolades after her death in 1936. She was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1973, recognizing her pioneering work in education. The Perkins Institute for the Blind, where Sullivan studied and later taught, established an award in her name to honor exceptional educators.

Mark Twain, who admired Sullivan's work, dubbed her "the miracle worker" - a title that stuck and later became the name of a famous play and film about her life with Helen Keller.

Annie Sullivan as a Symbol of Dedication

Sullivan's unwavering commitment to Helen Keller's education made her a symbol of perseverance and dedication. Her innovative teaching methods, which emphasized experiential learning and tactile communication, revolutionized approaches to educating those with disabilities.

Sullivan's own journey from poverty and visual impairment to becoming a renowned educator inspired many. Her life story demonstrates the power of education to transform lives and overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

Continued Relevance in Education

Sullivan's methods remain relevant in modern special education. Her emphasis on individualized instruction and adapting teaching strategies to meet unique student needs aligns with current best practices.

Many schools and programs for visually impaired and deafblind students incorporate elements of Sullivan's tactile signing and experiential learning techniques. Her approach to breaking down communication barriers continues to inform strategies for teaching students with multiple disabilities.

Sullivan's legacy also extends to advocacy for disability rights and inclusive education, areas where her work with Helen Keller laid important groundwork.